It’s often said – and rightly so – that primary source material is a godsend not only to the historian but also to historical novelists. As well as giving us an idea what happened, primary sources can also provide a valuable insight into the mind-set of those who lived in the period we are trying to present to the reader. Letters, diaries and court records – they all have their value to the historical fiction writer.

The only drawback of primary sources is that they can be unreliable and some of the least reliable are chronicles. Yet chronicles are usually a good starting point to give the student of history a general idea of what happened – or so I thought until I explored the Yorkshire revolts of 1469.

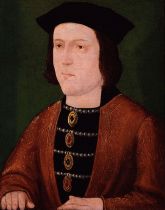

Last month I began some serious research for the next book in the Rebels and Brothers series which is set during the Wars of the Roses. In doing so I stumbled across an example of how utterly bewildering some chronicles can be. I was interested in the revolts in Yorkshire which culminated in the Battle of Edgecote in July 1469 where some leading noble supporters of Edward IV were killed.

All I wanted to know was what happened, but it wasn’t as simple as that. At first I consulted the accounts of historians but found them sparse and contradictory. When I visited the original sources I realised why, because the sources do not agree on much at all. They don’t agree on the timing, the people, the places, the size of armies or the routes taken by the rebels. Crucially, the identity of at least one of the rebel leaders is still a mystery – and likely to remain so. No wonder the historian, Charles Ross, refers to “total confusion amongst contemporary chroniclers.”

We do not even know for certain how many revolts there were: one, two or three. Historians, in an effort to make sense of the chronicles, tend to suggest three but no single chronicle suggests three! Some chronicles, such as the contemporary Brief Latin Chronicle and Polydore Vergil’s sixteenth century, English History, only describe one revolt but it is not the same revolt as the other chronicles describe!

Usually with rebellions there are some surviving court records which tell us about those who were condemned for their part in the events, but in the major revolt of 1469 the rebels won, so none of them were indicted!

With only a flimsy outline of the events I looked at the sources in detail to try to add a little flesh to the bones – fat chance! The problem with the chronicles is that, if they are all taken together, they do not give a credible narrative of the events – they cannot all be right! One is thus forced to “pick’n’mix” from them – abandoning a date here, a name there, or an event somewhere else.

One certain fact is that in the spring and summer of 1469 there was at least one revolt originating in Yorkshire. This revolt was apparently led by a certain “Robin of Redesdale” – also referred to in some sources as “Robin Mend-All.” It was directed against the “evil councillors” of the king, such as the Woodvilles, principally Earl Rivers – father of the Queen – and William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke – the growing power in the Welsh Marches. Whether “evil” or not, Rivers and Herbert were no friends of Warwick and it appears that it was Warwick who was behind this revolt.

One certain fact is that in the spring and summer of 1469 there was at least one revolt originating in Yorkshire. This revolt was apparently led by a certain “Robin of Redesdale” – also referred to in some sources as “Robin Mend-All.” It was directed against the “evil councillors” of the king, such as the Woodvilles, principally Earl Rivers – father of the Queen – and William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke – the growing power in the Welsh Marches. Whether “evil” or not, Rivers and Herbert were no friends of Warwick and it appears that it was Warwick who was behind this revolt.

Some chronicles indicate that there was another rebellion in the spring led by “Robin of Holderness” which had more local aims such as the restoration of the Percy family to the Earldom of Northumberland. This rebellion was definitely crushed by John Neville, Earl of Northumberland – Warwick’s brother – so it does not seem likely that this one was fomented by Warwick. “Robin of Holderness” might have been executed depending on which Chronicle you believe. This second revolt causes confusion amongst historians because several chronicles roll both revolts into one.

Robin of Redesdale’s revolt was the more significant and more dangerous for Edward IV than the short-lived Holderness one. The chronicles differ about its timing: was it in the spring or summer? We are obliged to guess whether it had a false start in spring and then rose again in June or only occurred in the summer. What is agreed is that in June and July the rebels advanced southwards from Yorkshire. Edward IV was in the Midlands but he had few men with him and sent to William Herbert and Humphrey Stafford, the new Earl of Devon, to come north to confront the rebels. Herbert’s Welshmen and Stafford’s west countrymen encountered the rebels near Banbury and a bloody battle ensued.

The revolt had all the outward appearance of a popular uprising but we know it was engineered by Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, because we have firm documentary evidence of his involvement in drafting the rebel manifesto. Whilst Edward’s attention was on the Yorkshire revolt, Warwick was marrying off his daughter, Isabel, to George, Duke of Clarence, the king’s brother, in Calais. He then brought the Calais garrison across to Kent and raised more troops to join “Robin of Redesdale’s” rebels.

The revolt had all the outward appearance of a popular uprising but we know it was engineered by Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, because we have firm documentary evidence of his involvement in drafting the rebel manifesto. Whilst Edward’s attention was on the Yorkshire revolt, Warwick was marrying off his daughter, Isabel, to George, Duke of Clarence, the king’s brother, in Calais. He then brought the Calais garrison across to Kent and raised more troops to join “Robin of Redesdale’s” rebels.

It would be easy to say that Edward “took his eye off the ball.” Should he not have realised that his chief magnate was plotting with his own brother against him? Well, quite a lot of people were fooled by Warwick’s behaviour during 1468 and the spring and summer of 1469 when he appeared to be working for the king with tireless energy and application. In fact, he was plotting the destruction of the Queen’s family, the Woodvilles, and the rising power of William Herbert.

So who was this “Robin of Redesdale”? The sources are little help here either but the smart money seems to be on either Sir John Conyers who was a relative of Warwick’s by marriage – or his son, John, or perhaps his brother William. William Conyers was killed at the battle of Edgecote on 26th July where the rebels triumphed over Herbert. The Conyers family were staunch Warwick supporters but there is no conclusive evidence as to which man was “Robin.” We’ll probably never know for sure.

Why are chronicles in general, and these chronicles in particular, so contradictory?

There are several reasons. The most obvious one is that most chronicles are written by a third party – an observer with no direct involvement in and often no personal knowledge of the events. In this case the perspective of the observers is very one-sided. Of the ten or so chronicles and fragments of chronicles with anything to say about these events, only one, John Warkworth’s Chronicle, is written from what you might call a “northern” perspective. The rest are written by southerners some of whom, such as the writer of the Croyland Chronicle, are usually very hostile to northerners. Most writers knew very little about what happened in the north and when they did not know they often guessed.

Secondly, at least half of the sources were written in the sixteenth century long after the events occurred. They may have spoken to some eye witnesses but it is doubtful. A great deal had happened since 1469, in particular the accession of the Tudors. The events of the Yorkist period were often portrayed as a chaotic contrast with the Tudor peace.

Another factor influencing the perspective of chroniclers was that the heavy casualties at Edgecote were not felt at all in most of England. Those who bore the brunt of the rebels’ anger were not Englishmen of the Midlands, London or East Anglia. Most of the fallen were Welsh or from the West Country – which to a Londoner might as well have been Greenland! There were no wounded men coming back to tell their tales in the taverns of the south-east.

The wounded were in fact heading back to Wales and it is no surprise that there is a wealth of evidence from Welsh poetry of the time which describes the exploits of the Welsh soldiers at the battle of Edgecote.

How do historians make sense of this tangled web of sources? Basically, they have to miss some things out and make other things up so that what they end up with is a sequence of events which is logical. This means they devise a scenario that has three revolts and two leaders – a scenario which none of the chronicles actually describes!

For the historian this is very unsatisfactory but for the historical fiction writer, it’s marvellous. I will have more freedom to invent than I know what to do with!

Further study:

Those interested in a more detailed examination of both the events and the sources could read K R Dockray’s Paper on The Yorkshire Rebellions of 1469 and a Paper by Barry Lewis called The Battle of Edgecote or Banbury (1469) Through the Eyes of Contemporary Welsh Poets.

And finally… please visit the links below where a glittering array of historical fiction writers have posted some corkers!

- Helen Hollick : A little light relief concerning those dark reviews! Plus a Giveaway Prize

- Prue Batten : Casting Light….

- Alison Morton Shedding light on the Roman dusk Plus a Giveaway Prize!

- Anna Belfrage Let there be light!

- Beth Elliott : Steering by the Stars. Stratford Canning in Constantinople, 1810/12

- Melanie Spiller : Lux Aeterna, the chant of eternal light

- Janet Reedman The Winter Solstice Monuments

- Petrea Burchard : Darkness – how did people of the past cope with the dark? Plus a Giveaway Prize!

- Richard Denning : The Darkest Years of the Dark Ages: what do we really know? Plus a Giveaway Prize!

- Pauline Barclay : Shedding Light on a Traditional Pie

- David Ebsworth : Propaganda in the Spanish Civil War

- David Pilling : Greek Fire – Plus a Giveaway Prize!

- Debbie Young : Fear of the Dark

- Derek Birks : Lies, Damned Lies and … Chronicles

- Mark Patton : Casting Light on Saturnalia

- Tim Hodkinson : Soltice@Newgrange

- Wendy Percival : Ancestors in the Spotlight

- Judy Ridgley : Santa and his elves Plus a Giveaway Prize

- Suzanne McLeod : The Dark of the Moon

- Katherine Bone : Admiral Nelson, A Light in Dark Times

- Christina Courtenay : The Darkest Night of the Year

- Edward James : The secret life of Christopher Columbus; Which Way to Paradise?

- Janis Pegrum Smith : Into The Light – A Short Story

- Julian Stockwin : Ghost Ships – Plus a Giveaway Present

- Manda Scott : Dark into Light – Mithras, and the older gods

- Pat Bracewell Anglo-Saxon Art: Splendor in the Dark

- Lucienne Boyce : We will have a fire – 18th Century protests against enclosure

- Nicole Evelina What Lurks Beneath Glastonbury Abbey?

- Sky Purington : How the Celts Cast Light on Current American Christmas Traditions

- Stuart MacAllister (Sir Read A Lot) : The Darkness of Depression

Thanks very much for this great post. After prehistory, WOTR is my second area of study but I am relatively new to it in comparison. A fascinating time

Thank you for filling in some of the pieces of the Yorkshire’s history puzzle for me.

Your post makes me wonder what future historical novelists would make of modern history events if the only source materials they had were our daily newspapers. I guess the biggest challenge for future writers will be excess of source material rather than lack of it, and how to choose what to use and what to ignore.

I’m sure you’re right about that. You could certainly see an historian of the future wondering if the Sun and the Guardian were describing the same event.

i liked the part about not even knowing how many revolts there were.. plus, of course, it doesn’t help that the leading men on two occasions shared the name Robin. That Warwick was quite the Machiavellian type, wasn’t he? Very interesting post!

A very enjoyable post and I enjoyed the illustrations as well.

Fascinating post – thank you for sharing!

Great post! As someone who studies the Dark Ages for use in historical fiction, I totally feel your pain about lack of clear information and conflicting material. But it surprises me such confusion exists in a time period that appears well documented. As you said, since you write fiction, the lack of clarity is a goldmine. Best of luck to you and happy Solstice.

Yes, usually the fifteenth century has more to offer in documentary evidence, though it is always patchy. Not quite as bad as the Dark Ages!

Fascinating stuff, but as you say, great for the historical novelist!

I completely agree with Nicole. It may be frustrating, but it’s a goldmine nonetheless.

I feel your pain — or glee, depending on how you look at it. One of my favorite things to do is to make up back stories that explain/fill-in accounts of 11th c events in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. Throw in the Saga accounts of the same events and it becomes an even bigger challenge! Enjoyed your post! Thank you!

Yes, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a bit of a tease at times, isn’t it.